The Greek Branch of the MGS

Past Events 2017 2016 2014 2013 2012 Older

November 2015

Workshop on propagation of bulbous plants from seed

In late November, 15 of us visited the nursery of MGS member Lefteris Dariotis, in Peania, where Lefteris demonstrated several techniques for the propagation of bulbs from seed. Below are my notes from the demonstration and photographs of his beautifully designed and maintained garden and nursery. Before we left Peania, Lefteris took us to see another garden in the neighborhood where he has begun installing drought-tolerant, mediterranean climate-adapted plants. In this garden, Lefteris did nothing to amend the hard-packed clay soils before he began planting and only waters enough to assist the plants in getting established. After a few years, he plans to stop watering. In addition to his expertise with bulbous plants, Lefteris also cultivates a large number of salvias. We’ll see if we can convince him to provide another workshop to share his knowledge of these plants in the spring.

Miscanthus and Pennisetum glaucum 'Purple Majesty' grasses,

a number of salvias (pink S. involucrata, purple S. leucantha,

wine burgundy S. 'Wendy's Wish' and S. splendens ‘Peach’),

orange Tithonia rotundifolia

Pink Salvia 'La Siesta', purple Salvia leucantha

and two ground-hugging Teucrium species,

T. pyrenaicum from the Pyrenees and T. aroanium

from the Aroania Mountains of Greece. Agapanthus

and Spanish lavender in the background

Notes on bulb propagation from seed:

Use fresh seeds. Depending on the species, bulbous plant seeds stay viable for more than a month or two (as in the case of the family Amaryllidaceae), or sometimes less, once they are taken from the seedpod. Other families, like Iridaceae and Asparagaceae (which includes genera such as Hyacinthus), produce seeds that remain viable for a number of years, but always give the best germination results when planted in the first year.

Collect the seeds when the pod starts to split in order to replicate the natural cycle of the plant.

Potting mix for bulb seeds: 50% peat (without weeds), very fine (Lefteris uses a German brand), and 50% very coarse river sand. Small bulbs are hard to find one or two years later if you have a coarse organic component in your mix. Lefteris has stopped using perlite in his potting mix because many young bulbs are the same colour and size as perlite, making them hard to pick out when it is time to re-pot them.

Drainage is very important for the seeds as they germinate and for the bulbs as they grow. Put a good five cm of perlite in the bottom of the pot.

Water the soil mix well before planting and wet heavily again well after planting, with a fine mist for small seeds. Take care to avoid rot with summer bulbs. Winter bulbs do not rot.

Bulbs grow best if planted densely. Lefteris sprinkles his seeds heavily on top of the potting mix and covers them lightly with the soil mix; bulb seeds do not need sunlight to germinate.

Planting Tritonia deusta seeds

Most bulb seeds germinate and sprout in one month. You must have a ten degrees C temperature difference between night and day. Bulbs stay outside in this climate (Athens). If there is no rain in winter, water the seedlings. Seedlings have better cold tolerance than big plants, in Athens Lefteris has never found the seedlings hurt by exposure to a short, light frost.

If planting in November, start to fertilize in February every 20-30 days until April with a fertilizer designed for tomatoes, but use half as much as you would for tomatoes.

Lefteris recommends using slug pellets, but he has never needed to use other pesticides.

Do not water bulbs in the summer, let them go dormant. Put most bulbs in shade in summer.

In one year you can harvest the bulbs. Dump pot into sieve and sift out the bulbs.

Small bulb species can stay in the original pot. Bulbs that grow into large plants need to be potted on.

Transplanting bulbs

Use a soil depth above the bulb 3 times the size of the bulb. Don’t worry about the direction of the bulbs, if you don’t have the patience to plant them the correct way, they will orient themselves. Lefteris puts a top cover of sand, 2-3 cm deep, to control weeds and to keep leaves that touch the surface from rotting (sand dries very quickly). Also the plants look nice and neat with a sand topping.

Ornithogalum dubium 'Yellow Custard' and 'Coconut Cream', illustrating

plants that like a sand topping to protect the leaves from rot

For planting sea lily (Pancratium maritimum) seeds, use mainly river sand with hardly any peat and double the depth of perlite drainage at the bottom of the pot. Leave these bulbs in same pot for two years.

Tour of the nursery section of the garden

Lachenalias and tritonias behind and Greek native drought-tolerant

seedlings in the front

Scabiosa crenata ssp. dallaportae, a very short

subspecies from the coasts of the Ionian islands

(centre),Salvia tingitana (upper left) and an unknown

mat-forming Stachys sp. from Turkey (lower right),

from the

drought-tolerant garden

June 2015

The olive groves of Lambros Vlachos, near Vrondamas, Laconia

Labros Vlachos, an enthusiastic olive grower with an obvious sense of fun and a love of life, made us very welcome at his olive farm. He holds strong principles which he combines with a passion for his land and his olive trees. ‘He cares about every leaf,’ says his friend Ina. It would appear that for over 40 years he has viewed the development of his olive farm as a challenge, a big adventure, and an indulgence of his passion. Economic factors and profitability may be secondary considerations but he suggested more than once that Anna, his partner, might be bringing some order and rigour to that aspect of the business.

In 1970, Labros returned to Lakonia from Chicago, where he had run a Greek restaurant with his cousin and uncle. He joined forces with his brothers to farm their family olive groves in the vicinity of Vrondamas, in the gently rolling hill country adjoining the lower valleys of the Evrotas River and its tributaries. The hot, dry summers and warm, wet winters are ideal for olive farming, but Labros does irrigate his trees throughout the year and productivity can be impaired by frosts which affect some pockets of land. In these parts of the farm he allows some top branches to grow longer to give some protection from the frost. The soil on his farm consists mainly of a sandy clay which is prone to bake hard and form deep cracks if not irrigated during high summer.

Labros has gradually bought out his brothers and acquired new parcels of land. He now farms 300 stremmata (30 hectares) which contain 10,000 olive trees. Most of these are 40 years old and of the Kalamon variety, which are farmed for their eating olives. There are also Koroneika trees grown for olives which are pressed to make oil, and some wild olive trees which are also farmed for their oil. Seven thousand trees were lost in the wildfires of 2008, most of which have been revived through controlled re-growth or grafting. In some cases, replanting has taken place with a spacing of seven metres being the desired norm. The Kalamon olive trees are kept large with a spread of six metres and a similar height. Labros adopts an empirical approach to improving yields of olives, combining close observation of regularly productive trees with scientific analysis of soil and geology, and with an open-minded attitude to opinion and advice from employees.

Irrigation is mainly during dry summer months. In September/October, when the olive fruit is maturing, irrigation is at the rate of three cubic metres of water every ten days. Limited watering also takes place in the winter months, primarily to ensure that fertiliser applied on the surface (a recycled mulch/compost obtained from shredding the pruned branches, plus poultry manure) reaches the roots. Initially, water was obtained by pumping it from the Evrotas River or one of its tributaries. Now it is obtained from a 200m-deep borehole on the property. The irrigation water is distributed by a network of plastic pipes suspended above ground level. The nozzles have to be checked regularly to clear any blockages caused by silt in the water.

The main pests (dakos or olive fly, mildew etc.) are controlled by spraying. Copper sulphate solution and ‘Surround’ are two of the sprays Labros uses. He sprays mainly in July, but also earlier, when the flowers set.

Harvesting of the Kalamon trees begins in October and involves an army (60 or so) of casual labourers (mainly Afghanis). The branches of the trees are shaken by machinery to release the ripe olives. Note: eating-olive trees can rarely be picked all in one go. Like plum and cherry trees, they have to be revisited several times to harvest only the ripe fruit. The olive harvest for oil starts in mid-November.

Pruning is done mainly in the spring, following the harvest. Labros prefers not to prune in the summer or at harvest time. He admitted to a conservative attitude to pruning, although this has softened in recent years. The next season’s fruit develops on new growth or on one-year-old growth that has not fruited, so branches that have borne fruit are pruned. New growth is thinned to open up the tree, allowing the sun in to ripen the olives. Small, wispy branches are also removed. The aim is to provide a microenvironment where conditions favour the formation of ripe olives of a good size which can be picked safely and efficiently, and to minimise the effect of a year of low yield following a high yield year (the norm for olive trees, which are like apple trees in this respect).

Thanks go to Ada Kopitopoulou for arranging the visit, and to Martin and Jeswyn Jones for helping her. Thanks also to Anna and her helpers (especially Ada and Ina) for the tremendous picnic in the shade of the trees outside the little church of Agia Elessa, to Yiannis for his energetic display of pruning, and for the gifts of jars of Kalamata olives. Most of all a debt of gratitude is owed to Labros Vlachos for his warm hospitality and the sharing of his knowledge and experience.

John Hayes (with a few additions from Martin and Jeswyn Jones)

April 2015

Visit to the Valley of the Muses

According to its most famous son, the poet Hesiod, his native village of Askri at the foot of Mt Helikon was ‘a cursed town, bad in winter, unbearable in summer, pleasant at no time.’ But on the last Saturday in April, the area around it, dedicated to the Muses, could not have been more agreeable for our band of explorers. Although slightly overcast, no cruel winds disturbed the darling buds, and the brief shower that had muddied our cars on the drive up to Thebes from Athens went elsewhere. In fact, it was perfect walking weather.

We met our local member Christine Easthope at a spot off the National Road, and then followed her to a most unexpected idyllic new café, Limni Mouson, by a pond at Askri, midway between Aliartos and Thebes. There she gave us a wonderful hand-drawn map of the landmarks we’d be visiting or glimpsing in the Valley of the Muses, along with a description of the Muses’ attributes to refresh our memories and a list of some of the plants in English and in Latin that we’d be encountering. She then introduced us to our guide, Yannis Peppas, a retired army officer with an infectious passion for the rich history of his birthplace. We looked at the map together and then took off for our first stop, the ancient theatre on the slopes of Helikon.

Nothing remains of the theatre (3rd century BC) except for the hollowed cavea, but we arranged ourselves in what would have been the upper tiers while Yannis stood way below and gave us a talk on the mythical and factual background of the area. Even though the French excavators in the 1890s had either destroyed or removed most of the antiquities, the acoustics and atmosphere had survived intact.

View from the upper tier of the ancient theatre with Yannis Peppas

We learned about Hesiod, a slightly younger contemporary of Homer and the first person to refer to his countrymen as Hellenes rather than Myrmidons or residents of a particular region. His father had migrated here from Asia Minor, attracted by the promise of rich soil, and Hesiod wrote of practical matters in his Works and Days and of the birth of the gods and myths in his Theogony. Apparently the Thracian shepherds who founded Askri had brought the worship of the Muses from Olympus to Boeotia, but it was Hesiod who expanded their number from three (History, Memory and Song) to nine, and he said that they appeared to him while he was tending his flocks. Both the theatre and the barely distinguishable sanctuary below it were used for the Mouseia, contests devoted to music and poetry, as well as Erotica, games in celebration of love, held every five years, and organized, appropriately, by the Thespians (denizens of the nearby village of Thespies).

Yannis’s talk was sprinkled with evocative references to mythical and historical figures from Narcissus and Teiresias to Sylla and Constantine the Great, both of whom plundered the area. The spring on top of Helikon, Keats’s Hippocrene, was so named because Pegasus had created it with the tip of his hoof. It and a second spring, Aganippe, were sacred to the Muses, and the whole area, fertile and well-watered, must have been glorious. Temples to Zeus and other gods abounded, as did statues of the nine goddesses by famous sculptors, as we know from Pausanias and inscriptions on the bases now in museums. In time churches replaced the temples, and the Frankish conquerors also left their mark in the form of stone towers. Of Ottoman rule, nothing is visible, and today’s village is pretty, but humble, with a bust of Hesiod and a replica of his famous plough in the main square and lilacs blooming in small gardens.

A full history can be read online in Greek on the Askri society’s website.

Our heads full of information, we picked our way down the hillside to the sanctuary proper, stopping to photograph or admire the rock roses (Halimium halimifolium), purple salsify (Tragopogon porrifolius), yellow bee orchids (Ophrys lutea) – once we’d seen one, we saw a dozen – a sole Ophrys speculum, not to mention lots of purple vetch, broom, gorse, wild pear, yellow patches of buttercups, a few borages, and many clumps of Euphorbia acanthothamnos, E. characias and E. helioscopia, among the most notable flora. Down by the vestigial sanctuary foundations, a smattering of slender crimson orchids, Dactylorhiza sambucina, aroused cries of glee.

Ophrys lutea

Dactylorhiza sambucina

Back on the road, we piled back into our cars and drove to a 9th-century church dedicated to the resurrection of Christ, passing field after field of beautifully tended vines studded with pale shoots, and wooded hillsides that had us marvelling at their fifty shades of green. The church had been lovingly restored, but we were even more impressed by the mighty oaks near it.

Askri is famous for its vineyards and its Frankish towers

Oak trees

(Photo by Olof Kargsten)

From there we moved on to a place where two small rivers met, the Episkopi and Permessos, whose banks were thickly sprinkled with horsetails (Equisetum), looking remarkably like pine seedlings. Wild cherry trees formed a curtain of white on one side, while two pink and black sweetpea flowers managed to avoid being squashed on the other. The trill of nightingales bade us goodbye.

Horsetails (Equisetum)

The beautiful sweetpea, Pisum sativum ssp. elatius

By the time we arrived at Askri for our taverna lunch, we were ready for sustenance, of course, but also hungry for more adventures. Yannis and Christine kept telling us of other walks and sites that will be just as interesting and attractive in autumn, so although our morning’s exertions were agreeably rewarded by our salads, chops and cheeses, our appetites remained whetted for the next excursion.

With many, many thanks to Christine Easthope and Yannis Peppas and hopes that we shall be visiting again before too long.

Text and photos by Diana Farr Louis, except for one noted by Olof Kargsten.

March 2015

Tour of a Private Garden by the Sea

Fifteen of us travelled to Rafina on a Saturday morning to visit the garden of Diane Katsiaficas and Norman Gilbertson. To our pleasant surprise, the visit also included a tour of the house and Diane's studio. The weather that day was a bit overcast with light rain, but I had made a preliminary visit a few days earlier with Sally Razelou and former branch heads Diana Farr Louis and Frosso Vassiliades, when it was sunny. You will see photos taken on both days, including a photo of Sally in a vacant lot near the house where she was delighted to find so many native plants thriving, including Thymelaea hirsuta, Thymelaea tartonraira and Convolvulus oleifolius. Diana and Frosso made the initial contact with Diane in the autumn of 2014 and laid the groundwork for our visit in March.

A brief stop in a vacant lot to check the variety of native plants growing wild

When we arrived, we were treated to fresh muffins, coffee and tea in the living room with a double height ceiling full of light, artwork and books. A fire was lit to take off the chill from the light drizzle outside. We all wanted to know about the beautiful pottery on the table and Diane, a professor of art at the University of Minnesota, told us about her multi-year collaboration with potters on the island of Sifnos that began when she participated in a collaboration between artists from Athens and traditional Sifniot potters. That experience has led to an enduring friendship between Diane and Norman and three generations of potters of the Lembesis family.

View of the living room

Diane told us the story of acquiring the land and starting the garden. Norman and his first wife, Doreen Arditti, a Greek from Thessaloniki, bought the property in 1960 when Norman was working in Athens. It was at that time an abandoned vineyard with little else in the area. Subsequently, they moved to work in France, then Belgium, then, after Doreen passed away, Norman volunteered in management at the American Farm School in Thessaloniki. As a result, they did not develop the land. The idea of what to do rested for many years in Norman's mind. After Diane and Norman married in 1989, he showed Diane the land and shared his long-term dream of creating a little paradise on this acre of special ground. Garth Rockcastle, an American architect and colleague of Diane's at the University of Minnesota, designed the house with every respect for its location, legality and as a locus around which the garden could develop. They began in 1991, moved in in 1992 and the garden continues to evolve and mature.

View of the house from the edge of the bluff

View of the garden from the ground floor terrace

View of the ground floor terrace with salvaged chandelier

Before we moved outside, Vangelis, Norman and Diane's long-time gardener and friend, told us about their collaborative work in the garden. Not only has Vangelis helped with plant selection and care of the garden, he is also responsible for all the stonework, including retaining walls, paths, raised beds and a pavilion for the outdoor fireplace. The garden has many different areas and many types of plants including fruit trees, succulents and natives, many self-introduced. Throughout the garden you find the addition of sculptures and objects related to Diane and Norman's travels or items given to them by friends. For example, there is a bed of large, smooth white marble stones that were once inside the foyer of a friend's home. They were transferred to the garden when those friends redesigned their foyer.

Vangelis tells us about the design and maintenance of the garden

All three trees (Punica granatum, apricot and Cercis siliquastrum) are self-seeded

Many of the cistuses are self-seeded

Raised vegetable beds in the citrus grove

Before we left, Diane gave us a tour of her studio where she showed us works she has done in paper, etched on plexiglass and laser-cut in silk fabric. Diane is a 'visual storyteller'. Her works reflect a progression through a variety of media using photography, sketching, painting and laser cutting with highly sophisticated machines. Diane is represented in Athens by Ekfrasi-Yianna Grammatopoulou Gallery. She also has her own website.

Diane showing us her artwork

After we had spent about three hours at the house and garden, most of us, including Diane, Norman and their friend Phaidon, who was visiting from Thessaloniki, moved on to share a delicious meal at the taverna Kalo Kathoumena in the plateia of Rafina. After this visit, everyone agreed that spending time with Norman and Diane in their house and garden was a wonderfully warm and touching experience.

Text and photo by Robin McGrew

March 2015

A walk on Mt. Hymettos from Koropi

On Monday, 16 March, twelve of us went for a walk on Mt. Hymettos led by Nikos Pavlidis. Nikos has been working for several years in this part of Hymettos to improve and install paths that trace the ancient way people crossed from one side of the mountain to the other. The day was partly sunny and only slightly windy - perfect for walking. We met outside the village of Koropi and drove a short way up into the mountain.

The area showed signs of use by motorbikes but, fortunately for the tranquillity of our walk, there were none in sight on a Monday morning.

At the start of the walk: the area just outside Koropi is quite untouched

Before we started up the path, Nikos gave us a brief history of the area and described the project undertaken on behalf of the town of Koropi to reopen the path tracing the Sfittia Way. The ancient road took its name from the settlement of Sfittos, which was located to the west of Koropi. It connected the Mesogeia plain, starting at Thorikos where an ancient theatre can be seen today, with the coastal road called the Asti Way which led on into Athens. It is mentioned in mythology/history as the road taken by Pallas and his sons when they went to attack Theseus who had just become king of Athens. Over the years, many parts of the road on the plain were incorporated into the paved road system, but the track over Hymettos via the Stavros pass was too steep for this. Nevertheless, within living memory the route was used by farmers with fields on the slopes and by some traders, most notably fig-growers from the Vravrona area, who carried their high-value crop by mule over the mountain track to the coastal suburbs.

In order to reopen the road, Nikos, together with the professional path builder Fivos Tsaravopoulos and residents of Koropi, first searched for signs of where the old path had passed. One obvious place on the route was a well/cistern which had been dug to collect the rainwater running down a gully so that passers-by could be refreshed. The aim of restoring the path was to open the eastern side of Hymettos to hikers, and indeed a whole network of paths has now been restored. You can find the paths here.

The way was steep but the footing was solid. No one had any trouble making it to the saddle where we stopped to have a look around and eat some tiropita, generously provided by Fleur and carried by Nikos.

Starting up to the saddle: note the naturalistic creation of the path

A break for water and tiropita at the saddle

We descended the other side of the saddle, again steep but without difficulty. As we went down and around, we could glimpse Athens in the distance. On the mountain it was quiet except for the call of birds and insects. One of our group spotted a bird's nest on the ground and a large tortoise starting to move about in the sun. Several times we stopped to look at wild flowers.

The path back to the saddle, not a soul in sight

yet surrounded by metropolitan Athens

Alkanna tinctoria

Descending steps created by Fivos, we stopped to look at

Helianthemum hymettium growing out of the rock face

Centaurea, unknown species

We then walked up another small path to look at an extremely deep hole in the ground, which we learned is the Thrakia sinkhole. Peering from the edge of the 30 m deep hole, it is impossible to see the glories concealed at the bottom. Cavers descending into it have found on the downward side a gallery leading into a chamber the size of a small concert hall. This part of Hymettos is very rich in caves because of the geology of the mountains – mainly marble and dolomite. Needless to say, we did not descend into the sinkhole on this outing.

A very deep natural hole in the ground: the photographer

did not dare lean over to photograph it adequately

The return to the cars was done at a slightly slower pace, but the weather held and all arrived back at our starting point very happy and with many thanks to Nikos and Fleur for arranging this outing. As a side trip, on the way to Kostas’ taverna in Paiania for lunch, Nikos took some of us to a field where the day before he had discovered a large number of orchids flowering under the olive trees. The experienced botanists in our group were excited to see so many specimens in one place. I was delighted by everything we saw that day and happy to find such a place just on the other side the mountain from the Athenian metropolis.

Himantoglossum robertianum under the olive trees

Text by Robin McGrew, Fleur and Nikos Pavlidis

Photos by Robin McGrew

February 2015

Composting Workshop in Paleo Psychiko

With the EU imposing fines on Greece’s illegal landfills and at the same time mandating huge reductions in organic waste throughout Europe this year, it seems all the more urgent for the MGS to do its part to encourage composting among Greek members. Of course, many members already compost and have been doing so for years, so we are broadening our efforts to increase awareness among non-members as well.

Composting is pretty easy if you can do it outside. Almost every garden has some corner where you can hide a pile of kitchen waste or dig a hole for it, combine it with leaves, dead heads, stems and stalks, and leave it to turn back into rich soil.

Using a fellow member’s garden, Robin McGrew told us about outdoor methods before handing the lawn over to Cornelius Vekkos, a composting guru who has a shop in Melissia, but is willing to give advice free of charge. Before showing us a bin, so completely concealed that you would never suspect its existence, Robin demonstrated the use of a small shredder that is just the ticket for cutting up thin branches and tough stalks before adding them to the pile.

Robin demonstrating the use of the shredder

She said that almost any organic matter can be composted, apart from a few aggressive weeds like oxalis that ‘should be strictly isolated’. Our hostess noted that she never adds the grass from cutting the lawn since it has a tendency to turn slimy.

Because her garden is relatively small, she puts all the waste, from both garden and kitchen, into a plastic bin with an open bottom to allow worms and other beneficial organisms to enter and help decompose the waste. The ready compost is collected via a removable panel at the bottom of the bin. She does include some citrus peels, because although they are acidic and slow the process down, the addition of leaves compensates, raising the temperature while masking the unpleasant smell and keeping the fruit flies away.

Almost any organic matter can be composted

Once we had all inspected the bin, Robin showed us a long metal ‘corkscrew’, which can be used to stir/mix up the contents. Ideally, a pile or bin should be watered if it gets dry and forked over to introduce air and hasten the process. You can also sieve the harvested compost to remove sticks and other large pieces before adding it to your soil.

As Cornelius Vekkos said, ‘composting is all about water, air and patience. In a garden, you need air, but if all you have is a balcony and kitchen waste, then you need a wormery. Worms aren’t necessary in an outside bin/heap – they’ll come on their own, along with chafer beetle larvae’ (which our hostess removes and leaves for the birds – in the ground or pots they may eat plant roots). As for water, you can keep your outside pit compost moist by covering it with wet cardboard in summer or an old rug or towel.

A wormery is ideal for apartment dwellers, especially if you can keep it in a place with a constant temperature, like a garage or basement, because the worms do not appreciate the heat, cold or rain. Using a 100-litre bin to show us, Vekkos said it can process 300 kilograms of food waste. As an experiment, he has had his for well over a year now without emptying it. But he does extract the ‘tea’ from a spigot at the bottom, which, diluted with water, makes excellent fertiliser. Although under ideal conditions each worm will produce 200 offspring, there are certain foods they don’t like, such as high acidity citrus and tomatoes. To combat acidity, you can either add lye or eggshells. And to cope with excess moisture, add some shredded newspaper.

After describing what’s needed to get a wormery started – Vekkos sells a complete kit, container, worms, lye for 120 euros with a discount for MGS members – he moved on to bokashi. An anaerobic system using microorganisms, bokashi can break down meat, fish, citrus, banana peels… anything at all in just 20 days. It does not produce compost; instead, the contents should then be added to a wormery or compost bin before putting it in the soil.

Vekko and his wormery kit

The demonstrations were accompanied by lively conversation, questions and answers, as well as luscious refreshments. You can find lots of information about composting on this website, but there is nothing like seeing the different methods in practice and talking to an expert.

We plan to hold other workshops later in the year, in the centre of Athens and in the southern suburbs. Please contact Robin McGrew if you are interested in hosting or attending a workshop

For more information on bins and equipment, you can view Cornelius Vekkos’s website, or contact him.

Text and photos by Diana Farr Louis

February 2015

Walk through the Philodassiki Botanic Garden

Twenty members were met by our guide and garden custodian, Sophia Stathatou, and given an introduction to the history and philosophy of the garden which was established in 1947 on a site overlooking the Monastery of Kaisariani. There is an excellent website here with information about the garden, its physical data, plant collections, conservation and educational programmes etc. and another here with additional historical information about the forest, the garden and the monastery.

At the entrance of the garden

The garden exists for education and pleasure and to preserve 400 plant species from the

Peloponnese, the Aegean and Crete.

Hyacintoides sp.

Walking through this botanic garden is a unique experience as the planting, the altitude and the terrain take you along a hillside path on a beautifully constructed stone stairway, not through a carefully laid-out garden. There is something special to look at every step of the way and we were impressed by the carefully chosen plantings and the work done by so few people to create this very unique treasure of a garden.

A gentle path with spring greenery

The well-stocked nursery of plants for sale

A glimpse of the Byzantine chapel at the Monastery of Kaiseriani

Text by Vina Michaelides, photos by Loukia Konari.

February 2015

Walk through the Ancient Agora of Athens

On Sunday, February 1, 34 members met for a tour through the Ancient Agora led by landscape architect and MGS member, Simon Rackham. We assembled near the small church of the Holy Apostles inside the Agora archaeological site on a rather warm but misty morning.

Gathering for the walk

(Photo by Christa Vayanos)

As we started off, Simon gave some background information on the archaeological excavations. When the American School of Classical Studies was carrying out the excavations from 1931 to 1957, the decision was made to dig back as far as possible to classical antiquity – 5th to 4th centuries BC - and, with a few exceptions, to remove buildings and structures from later periods.

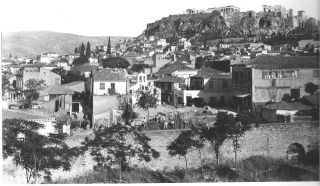

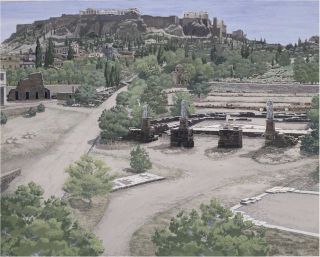

View of the Agora site before excavations began

(Photo from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

The higher ground on which we were walking reflected what was found during the excavations: that the ancient levels of the Agora varied from one to two metres below present ground levels on the south and west of the site (slopes of the Acropolis and mound of the Thisseion temple, to a maximum of 12 metres below present ground level on the north side of the site – the level of Apostolou Pavlou road. From this higher ground along the southern boundary, we had a very pleasant overview northwards of the whole site towards the road/railway line cutting. We turned downwards to our right, crossing the Great Drain that traverses the Agora, and then starting upwards again on the slope of the little hill crowned by the beautiful Thisseion (correctly, Hephaisteion) temple.

View from the south to the Temple of Hephaistos

(Photo by Christa Vayanos)

The original planting plan for the Agora excavations, drawn up by a very eminent landscape architect Ralph E. Griswold, was to plant vegetation known or reasonably assumed to be known and used in classical antiquity. This vegetation – trees, shrubs, etc. - was to be planted along the perimeters of the site, as ‘framing’ for the exposed foundations of the ancient buildings and along paths constructed by the archaeological team for the convenience of visitors who were expected to visit once the excavation work was completed. The trees and shrubs were planted partly to beautify the area and partly to remind the visitors of an essential, though not often remembered, element in the ancient setting, which was not a desert. The intention was that the foundations and known perimeters of the ancient buildings that had been exposed by the digs should be kept clear of vegetation or covered only by mown grass, so that their outlines and layout were clear and comprehensible.

On the higher ground – south perimeter, hill of the temple of Hephaistos - were planted carobs, pines (Pinus halepensis and P. pinea) and cypresses. The lower-lying areas were to be planted with willows (Salix caprea and possibly other species), planes and poplars, especially around the Great Drain. One of the few exceptions to the rule that the plants should date from classical antiquity in Greece was the planting of a palm tree near the little church of the Holy Apostles (now sadly lost to the depredations of the red palm weevil). There were also olives and various small oaks.

Along the sides of the temple of Hephaistos were found double rows of ancient planting holes and pot bases from two periods of antiquity – the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. These lines of planting are now echoed in double rows of low hedges of clipped (dwarf?) pomegranates and Viburnum tinus, now intertwined with convolvulus and other hedgerow plants. On the sides of the temple mound and the paths leading down into the lower part of the site are big masses of viburnum, medicago, lentisc, some columnar pines and, when we were there, airy waterfalls of white weeping broom (Retama raetam).

We walked down towards the site of the monument to the Eponymous Heroes and the altar of Zeus Agoraios. In this flat central area are olives, planes (P. orientalis), oaks and big bushes of lentisc and oleander, among others. Nearer the railway line there are big stands of acanthus. We paid very little attention to the area round the Stoa of Attalos, although there is a lot of vegetation there. Probably because our visit was very early in the year, we saw few small, flowering herbaceous plants or bulbs, although Simon mentioned that he has seen small scattered groups of blue Muscari, usually in March, over the rocky slopes below the temple of Hephaistos and in the gully running up to the Acropolis entrance.

During the walk, Simon described the course of the excavations and the intention of the planting plans, pointing out plants of interest. Simon’s comments and observations were most interestingly fleshed out by Jim Wright, the current head of the American School of Classical Studies, who was walking with us. At the end of the tour – and actually on the other side of the railway line outside the site that is open to the public –Dr. Wright showed us where excavation work is progressing (slowly, because of delays in enforcing the demolition of two remaining modern buildings) on the famous Painted Stoa (Stoa Poikile).

From our overview of the Agora site, it is obvious that the originally planned perimeter and ‘framing’ vegetation has been allowed to grow too exuberantly and has, to a considerable extent, obliterated the careful plans of Ralph Griswold. Although on blazing summer days the extra shade is appreciated by visitors, the fact that the vegetation has expanded so much and grown so tall means that it no longer frames the ruins as intended, but actually obscures their outlines. This makes it more difficult for the non-specialist to comprehend what was already a diverse and confusing assemblage of public buildings from different periods of time.

After the tour of the Agora we reconvened in a meeting room above a tavern in the Thisseo area, where Simon gave us a slide presentation illustrating the course of the excavations and plantings at the site. The original planting plans – beautifully hand-drawn and painted by Griswold - made the layout of the Agora site more comprehensible. Regrettably, a fair bit of imagination is now required to visualize the site as it was originally intended to be presented to the public. Griswold's projected graceful lines of columnar pines, etc. are now hard to spot.

Photograph before plantings were installed

(Photo from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

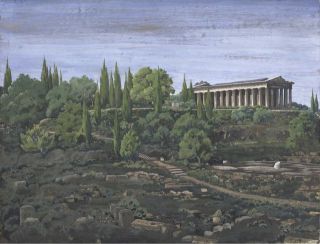

Griswald’s watercolour rendering of his design

(Image from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

Photograph before plantings were installed

Photo from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

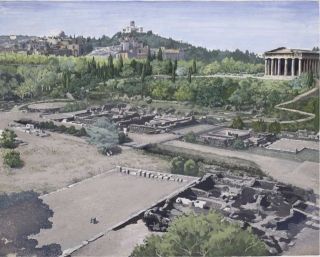

Griswald’s watercolour rendering of his design

(Image from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

Photograph before plantings were installed

(Photo from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

Griswald’s watercolour rendering of his design

(Image from Agora Excavations 1931-2006, CA Mauzy, ASCSA courtesy of Simon Rackham)

The planting up of the Agora site was a great exercise in promoting civic and national pride. Enthusiastic teams of boy scouts and girl guides in full uniform were involved, especially in planting the area round the temple of Hephaistos, the royal family was roped in to plant a symbolic tree and finance was provided for the project by philanthropic American millionaires.

In 1957, when the excavations and landscaping were completed, the American School handed over the maintenance of the site to the Greek Archaeological Service. There is obviously some considerable regret among archaeologists that the careful planting plans, intended to present the excavations to their best effect, have unfortunately fallen by the wayside over the intervening years.

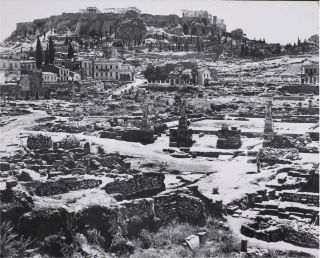

View of the agora today

(Photo courtesy of Simon Rackham)

Text: Margaret and Alexander Zafiropulo |